Politics

Biden will travel to Europe next week for an extraordinary NATO meeting

Published

3 years agoon

As the cost of living crisis deepens, you may be assessing your regular monthly outgoings and looking for things you can cut back on. If you are lucky enough to be a homeowner, your biggest monthly expense is likely to be your mortgage.

But will your lender allow you to reduce your payments if you explain that you are struggling? And how will that affect your credit record? Similarly, if you have life insurance or a pension, can you take a break from your payments, and what will the consequences be?

Taking a break from your mortgage

According to UK Finance, the trade association for banks, mortgage lenders should offer “forbearance” to any customer who is in financial difficulty or unable to make their mortgage payments.

This could take the form of an authorised payment holiday, where your lender gives you permission not to pay your mortgage for a short period, usually up to three months. Alternatively, with your lender’s permission, you may be allowed to reduce your monthly repayments.

It can be tempting to cut pension contributions when money gets tight but you are losing more than just your own contribution

These arrangements come at a cost. Any payment holiday will be noted on your credit record, which could have implications the next time you want to borrow money – you may, for example, be charged a higher interest rate. You will also be expected to pay back everything you have missed paying once you are no longer in financial difficulty. Your mortgage is likely to cost you significantly more in the long run.

Cancelling life insurance premiums

LV= allows this – but you can only benefit if your policy (for income protection, critical illness or life insurance) has been in force for a year or more, you have a good history of paying and are less than three months behind with monthly premiums. You must declare that you have suffered a significant drop in your income or that your usual earnings have stopped. The payment break will only be offered for a month at a time, for up to three months.

If you do find yourself in a position where you have to cut or stop your contributions, try to resume them as soon as you can.

For example, it says a 33-year-old with £250,000 of life cover, paying £21.86 a month, could reduce their payments to £4.17 a month for six months. However, the maximum that could be claimed during this six-month period would be only £10,000.

Cutting your pension contributions

You may also be considering reducing or stopping your pension contributions for a while. This may ease your financial pressures a little in the short-term but it will reduce your income in retirement.

Cutting £693 a year from your pension will mean £1,284 less goes into your fund. If that money manages to grow by 5% a year until you retire, the long-term cost is even greater. Hargreaves Lansdown, an investment platform, estimates that a 40-year-old basic-rate taxpayer who cuts back on their pension payments in this way – reducing their contributions by only £57.75 a month for only one year – would end up £4,569 worse off, before fees, by the age of 67.

You may like

-

US election live: Latest polls show Harris, Trump tied on election eve

-

Live Reporting

-

Live Reporting

-

US election live: Harris in Philadelphia, Trump to rally at Madison Square

-

Trump heads to key swing states as Harris makes star-studded final push

-

US election live: Trump in Vegas, Springsteen, Obama join Harris in Georgia

-

How Harris aims to keep drawing eyeballs as the hard campaigning begins

-

Donald Trump Vs Kamala Harris LIVE | The Big 2024 Debate | U.S. Election Latest

-

Harris-Trump debate: The economic stat that could swing the US election

-

‘Guerrilla projects’: Russia revels in US allegations of media warfare

-

Trump-Harris presidential debate draws estimated 67.1 million TV viewers

-

Ohio dad tells Trump to stop using son’s death for ‘political gain’

AP

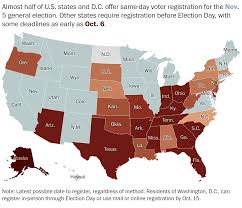

Not all elections look the same. Here are some of the different ways states run their voting

Published

7 months agoon

October 12, 2024https://imasdk.googleapis.com/js/core/bridge3.672.0_en.html#goog_793146038

0 seconds of 1 minute, 32 secondsVolume 90%

1 of 4 |

The U.S. general election this November will decide the country’s direction, but it is far from a nationally administered contest. Here’s a look at some notable caveats, edge cases, and oddities in certain states for the 2024 election.Read More

2 of 4 |

FILE – A man tallies the votes from the five ballots cast just after midnight, Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020, in Dixville Notch, N.H. (AP Photo/Scott Eisen, File)

3 of 4 |

FILE – Locked ballot boxes are seen in a room where the processing of absentee ballots takes place at City Hall, Monday, Nov. 2, 2020, in Portland, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, File)

4 of 4 |

FILE – A clerk with the New Hampshire Department of State unloads boxes of ballots, in Pembroke, N.H., for a forensic audit of a New Hampshire legislative election on May 11, 2021. (AP Photo/Josh Reynolds, File)

BY MAYA SWEEDLERUpdated 8:30 PM GMT+6, October 9, 2024Share

WASHINGTON (AP) — The U.S. general election on Nov. 5 will decide the country’s direction, but it is far from a nationally administered contest. The 50 states and the District of Columbia run their own elections, and each does things a little differently.

Here’s a look at some notable variations in the 2024 election:

Maine and Nebraska allocate electoral votes by congressional district

To win the presidency outright, a candidate must receive at least 270 of the 538 votes in the Electoral College. In 48 states, the statewide winner gets all of that state’s electoral votes, and that’s also the case in the nation’s capital.

In Maine and Nebraska, the candidate who receives the most votes in each congressional district wins one electoral vote from that district. The candidate who wins the statewide vote receives another two.

In 2020, Democrat Joe Biden received three of Maine’s four electoral votes because he won the popular vote in the state and its 1st Congressional District. Republican Donald Trump received one electoral vote from the 2nd Congressional District. Trump won four of Nebraska’s five votes for winning the popular vote in the state as well as its 1st and 3rd Congressional Districts; Biden received one electoral vote for winning the 2nd Congressional District.

Alaska and Maine use ranked choice voting

In ranked choice voting, voters rank candidates for an office in order of preference on the ballot. If no candidate is the first choice for more than 50% of voters, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Voters who chose that candidate as their top pick have their votes redistributed to their next choice. This continues, with the candidate with the fewest votes getting eliminated, until someone emerges with a majority of votes.

Maine uses ranked choice voting in state-level primaries and for federal offices in the general election. That means Maine voters can rank presidential, Senate and House candidates on ballots that include the Democrat and the Republican who advanced out of their respective party primaries, plus third-party and independent candidates who qualify.

The presidential ballot will include Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris, plus three other candidates. In the six years since implementing ranked choice voting, the state has used it twice in races for Congress in its 2nd Congressional District. The 2020 presidential race did not advance to ranked choice voting, with the winners of the state and in each congressional district exceeding 52% of the vote.

Alaska holds open primaries for statewide offices and sends the top four vote-getters, regardless of party, to the general election, where the winner is decided using ranked choice voting. In all legislative and statewide executive offices, Alaskans can rank up to four names that can include multiple candidates from the same party.

The exception is the presidency, which is eligible for ranked choice voting in Alaska for the first time. This year, there will be eight presidential tickets on the ballot, and Alaskans can rank all candidates if they choose to. The last time the winner of the presidential contest in Alaska failed to surpass 50% of the vote was in 1992, when third-party candidate Ross Perot won almost 20% of the national popular vote.

But in 2022, both Democratic Rep. Mary Peltola and Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski won their elections after both went to ranked choice voting.

Another wrinkle this year? In Alaska, where ranked choice voting was implemented by ballot measure in 2020, there’s a voter initiative on the ballot this fall to repeal it.

In California and Washington, candidates from the same party can face off

California and Washington hold open primaries in which all candidates run on the same ballot and the two top vote-getters advance to the general election, regardless of party. This year, there are two House races in Washington that include candidates of the same party, one with two Republicans and one with two Democrats. There are four in California: three with only Democrats and one with only Republicans.

The winning party in those six districts will be reflected in The Associated Press’ online graphic showing the balance of power in the House at poll close, rather than once a winner is declared because the party of the winner is a foregone conclusion.

Louisiana holds a ‘primary’ on Nov. 5

Louisiana holds what it refers to as its “open primaries” on the same day the rest of the country holds its general election. In Louisiana, all candidates run on the same open primary ballot. Any candidate who earns more than 50% of the vote in the primary wins the seat outright.

If no candidate exceeds 50% of the vote, the top two vote-getters advance to a head-to-head runoff, which can end up pitting two Republicans or two Democrats against each other. Louisiana refers to these contests as its “general election.”

That will change for elections for the U.S. House starting in 2026 when congressional races will have earlier primaries that are open only to registered members of a party. Certain state races will continue to hold open primaries in November, but the change will prevent future members of Congress from waiting until December — a month later than the rest of the country — to know whether they are headed to Washington.

Nebraska has two competing abortion measures on the ballot, but only one can be enacted

In Nebraska, any measure that receives approximately 123,000 valid signatures qualifies for the ballot. This year, two measures relating to abortion met this threshold.

One would enshrine in the Nebraska Constitution the right to have an abortion until fetal viability or later, to protect the health of the pregnant woman. The other would write into the constitution the current 12-week ban, with exceptions for rape, incest and to save the life of the pregnant woman.

This marks the first time since the 2022 Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade that a state has measures that seek to roll back abortion rights and protect abortion rights on the ballot at the same time.

It’s possible voters could end up approving both measures. But because they’re competing and therefore cannot both be enshrined in the constitution, the measure with the most “for” votes will be the one adopted, according to the Nebraska secretary of state.

Georgia holds runoff elections if a candidate doesn’t win a majority of votes

In primary elections, a handful of states, mostly in the South, go to runoffs if no candidate receives at least 50% of the vote. In races with more than two candidates, runoffs in those states are common. Several states held primary runoffs this year.

Georgia uses the same rules in general elections. The last three Senate races there went to runoffs because a third-party candidate won enough of the vote to prevent the Republican or Democratic nominee from exceeding 50% of the vote.

But this year, runoff possibilities may be confined to downballot races such as state legislature. There’s no Senate race there this year, and the U.S. House races have only two candidates on the ballot.

Texas, Florida and Michigan report a lot of votes before final polls are closed

This is common in states that span multiple time zones. In most states, polls close at the same time in each time zone.

The AP will not call the winner of a race before all the polls in a jurisdiction are scheduled to close, even if votes already reported before that time make clear who will win the race. So if there is a statewide race in a state where polls close at 8 p.m. local time, but some of the state is in the Eastern time zone and some of the state is in Central time zone, the earliest the AP can call the winner is 8 p.m. CST/9 p.m. EST.

The AP will still show the results as they arrive from counties with closed polls.

Some of the biggest states with split poll close times are Florida, Michigan, Texas and Oregon. Tennessee is an exception, as even though the state is in both the Eastern and the Central time zones, all counties coordinate their voting to conclude at the same time.

____

Read more about how U.S. elections work at Explaining Election 2024, a series from The Associated Press aimed at helping make sense of the American democracy. The AP receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Politics

World Insights: Can U.S. striking port workers win battle against automation?

Published

7 months agoon

October 3, 2024Source: Xinhua| 2024-10-03 14:06:45|Editor:

HOUSTON, Oct. 3 (Xinhua) — Picket lines were formed on Tuesday as about 45,000 dock workers walked out at 36 ports along the U.S. East and Gulf Coasts, demanding higher pay and ban on automation amid fears of job loss in an AI-driven future that extends far beyond the dock industry globally.

SHARP DISAGREEMENT

At Port Houston, striking workers, organized by the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), erected a large banner on Tuesday that read, “No to automation! Machines don’t have families to feed.”

“We are prepared to fight as long as necessary, to stay out on strike for whatever period of time it takes, to get the wages and protections against automation our ILA members deserve,” said Harold Daggett, the ILA president.

On the eve of the walkout, the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX), which represents the ports, had increased its offer on Monday, promising to raise wages by nearly 50 percent while keeping the limits on automation in place from the old contract and allowing semi-automation.

The union rejected the offer Tuesday, saying it fell short of workers’ demand.

The disagreement remains sharp as the labor union not only demands a 77 percent wage raise over the six-year life of the contract, but also a “total ban on automation” at ports, multiple U.S. media outlets reported.

As always, port operators, often representing large corporations, are keen to cut costs, increase profits, improve efficiency, and reduce the risk of accidents by adopting new technologies. Supporters of automation view it as a “must” and an inevitable step toward achieving these goals.

If the union gets most of what it wants from their employers regarding automation, U.S. ports will continue to lag behind international ones in terms of speed and efficiency, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a right-wing think tank, warned on Tuesday.

The labor union, focused on protecting workers’ rights, argues that corporations are dead set on replacing hard-working people with automation but “robots do not pay taxes and they do not spend money in their communities.”

“USMX is trying to fool you with promises of workforce protections for semi-automation. Let me be clear: we don’t want any form of semi-automation or full automation,” ILA leadership said in a September letter to members.

WHO CAN LAUGH AT LAST

Can union workers win the battle against automation?

In the coming weeks, port operators may raise their offer again as disruptions to the U.S. economy grow, the presidential election approaches, and the pressure to reach an agreement accumulates day by day.

The ports affected by the strike handle roughly half the country’s cargo ships. Analysis firm J.P. Morgan estimates the port work stoppage could cost the U.S. economy 5 billion U.S. dollars per day, not to mention fears of inflation and supply shortages. This strike could potentially become one of the most disruptive labor actions to the U.S. economy in decades.

The ILA last launched a major strike in 1977 against big containers, which were much easier to handle than individual boxes, saving costs and reducing the need for as many workers. The strike lasted 44 days and ended with a substantial pay raise and guaranteed income for union members, according to The Washington Post.

However, the 1977 strike did nothing to stop containers from dominating the shipping industry, which finds itself in a similar episode during the current strike: workers fighting to stop another technological advancement: automation.

Looking back at history, it is difficult to find an optimistic example of such resistance that has successfully preserved jobs as wished by the striking workers. One of the most famous early examples is the Luddite movement in 19th-century Britain, where textile workers protested automation by destroying machines but were eventually suppressed by the government.

It seems most likely that new industries and jobs will emerge from technological innovations, but only for those who acquire the necessary skills to thrive in the modern workforce. But what will happen to those who lose their jobs?

Industry experts suggest that the AI revolution and increased use of robots could drastically reduce the number of workers needed on-site at dockyards. Tasks like operating cranes, trucks, and gates will require fewer workers, possibly almost none.

American dock workers have already felt the impact of automation. A report from the Economic Roundtable found that automation removed 572 full-time-equivalent jobs per year at the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Los Angeles in 2020 and 2021.

“AUTOMATION UNEMPLOYMENT”

Beyond the shipping industry, automation is expected to eliminate millions of jobs in sectors such as transportation, retail, healthcare, law, finance, and many other professions, according to researcher Harry Holzer, writing for the Brookings Institution.

Local observers note that the labor market is becoming increasingly polarized. “Automation unemployment” is now a global challenge, affecting not only individual livelihoods but also social stability and economic growth.

“Global labor income share — the proportion of total global income that goes to workers — is shrinking,” said Celeste Drake, deputy director-general of the UN International Labour Organization (ILO), last month.

“The global trend of shrinking pay in heavily industrialized economies could be driven — at least temporarily — by tech innovations like automation and AI in the workplace,” warned the ILO official. “This needs to change because it’s increasing inequality, which disproportionately affects working people.”

One thing is certain: this strike will not be the last effort to resist automation. While automation is advancing with unstoppable force, the fight against robots replacing human workers will help shape our future in an AI-driven world, with serious consequences for global peace in the rest of the 21st century. ■

BBC

Trump dominates in rural America – will folksy Walz help Harris?

Published

7 months agoon

September 30, 2024

John Sudworth

Senior North America correspondent, reporting from Omaha and Hastings, Nebraska

In this closely fought US election, vice-presidential candidates JD Vance and Tim Walz were picked to sway Midwestern and rural voters who might be hesitating over Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. In Nebraska, owing to an electoral quirk, such voters could prove pivotal.

As an expert breeder, Wade Bennett can tell you the precise parentage of every one of the 140 head of Charolais cattle he keeps on a small holding on the edge of Nebraska’s rolling Sandhills.

Despite being a staunch Republican, he’s less certain, however, of the pedigree of the man once again vying for his vote.

Donald Trump, he says, would probably be “kicked out” of his voting shortlist if there were other conservative options available.

One of the least-populated states, Nebraska is, like much of rural America, not only deeply Republican but deeply Christian, too. And some here, like Wade, are uncomfortable with what they see as Donald Trump’s personal, moral failings.

But with Kamala Harris and a smattering of small-party candidates the only other options this November, Wade is putting his scruples to one side.

“Even as a Christian,” he tells me. “It is what it is.”

He’s focusing not on Trump’s character, but on his policies – and he likes the promises he hears to crack down on illegal immigration, cut the cost of living and put more tariffs on trade.

Even his slight hesitation, however, is enough to give Democrats hope.

The rightward drift of the American countryside over the past 25 years has been remarkable.

In 2000, Republicans had a six-point advantage over Democrats among registered rural voters, according to the Pew Research Center.

But by 2024, they had established a mammoth 25-point lead.

Even though only a fifth of Americans live outside the big towns and cities, the strength of their shift towards Donald Trump was key to his victory against Hillary Clinton in 2016.

But for Democrats, the rural vote is still worth fighting for, particularly where even small gains in already tight states just might make the difference.

So it’s no coincidence that both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump now have running mates whose white rural roots are being used to make the argument for who is best placed to speak on behalf of this country’s great Midwest.

Vice-presidential candidates don’t usually have much impact on how people vote, but when Tim Walz and JD Vance meet in a primetime televised debate on Tuesday night, they will be hoping their different backstories and visions resonate with voters still unsure about Harris, a California Democrat, and Trump, a New York real estate developer.

Walz, the current governor of Minnesota, was born in small-town Nebraska, and has made much of his background “working cattle, building fence”.

His time as a schoolteacher and football coach before politics, and his subsequent record in Minnesota, providing tax credits to families and free school meals, are precisely the kinds of things the Democrats hope will resonate with struggling rural voters.

Ohio Senator Vance, on the other hand, is a man who’s also made much of his rural roots, but with a far less optimistic framing.

Vance rose to national prominence with his best-selling book, Hillbilly Elegy, the story of his family’s origins in eastern Kentucky, their struggle with poverty, his mother’s fight with addiction and the joblessness and blight of Middletown, Ohio, where he grew up.

Where Tim Walz has emphasised individual freedom and what binds Americans, Vance has focused on a “ruling class” that he says has failed working families in small communities all over the country.

In writings and in interviews, he has stressed the need for individual responsibility, rather than welfare – although he does not support cutting programmes like Social Security. And he echoes Trump’s vision of protecting American jobs and workers with tariffs and border walls.

I meet 42-year-old Shana Callahan casting for catfish under a setting sun in the Two Rivers Recreation Area, just outside the city of Omaha. The cost of living, once again, is never far from mind.

“Everything costs more, everything sucks,” she says.

“I drive an F-150 and when Trump was in office, I was paying about 55 bucks for a tank of gas. Right now, it’s anywhere between 85 to 109, and, you know, the cost of groceries and everything has just gone through the roof.”

There were structural reasons for the depressed oil market during some of Trump’s presidential term, not least the Covid crisis, and prices had begun to climb steeply before he left office. Some economists also say President Joe Biden’s 2021 stimulus spending contributed to broader inflation.

But economics is a feeling in US elections, not a graph on a page, and Shana has made up her mind.

There’s nothing, she tells me, that would convince her to vote for Kamala Harris, especially not Tim Walz’s local backstory and his claims to represent people like her.

“For one thing, the man’s a goofball,” she says. “I can’t respect him. He comes out on the freaking stage like, ‘Oh, go, coach’.”

The story of JD Vance being raised by a grandmother because of the opioid crisis – which she knows from the film version of his book – resonates deeply, however.

“The beginning of the movie is like, you know, family is always going to back you up. I mean, that’s kind of the way it is out here.”

“I’m only 42 and I’ve had like, three friends die of fentanyl.”

Shana lives in the one small part of this vast, rural state that may find itself with an outsized impact on November’s election result.

Under the US system, each state is allocated a specific number of votes in what’s known as the electoral college. Presidential candidates need to reach 270 votes to win the White House.

Unlike most of the rest of America, where all the electoral college votes in each state go to the winner of the popular vote, Nebraska does things differently.

Three of its five votes are decided by whoever wins three individual districts.

Nebraska is a reliably Republican state but its second district – worth one vote – went to Trump in 2016, to Biden in 2020, and this time round there’s a scenario in which whoever wins it could win the whole election.

If Harris wins the Rust Belt swing states of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin and Trump takes the Sun Belt states of Georgia, North Carolina, Arizona and Nevada then the second district would provide the single tie-breaking vote.

District two is a microcosm of America, with the heavily Democrat-leaning city of Omaha balanced by the Republican-leaning outskirts and the countryside beyond.

In their backyard in the centre of Omaha, Jason Brown and Ruth Huebner-Brown are spraying giant blue dots on plain white lawn signs.

“We’re like a little swing state within a state,” Jason tells me. “It could absolutely, I guess you would say, be a history-changing moment. This could really be the ultimate one vote that matters.”

In an effort to keep the “blue dot” blue, the Harris-Walz campaign has been massively outspending Trump-Vance here, pouring millions into TV advertising.

Ruth tells me she believes it’s having an effect on the doorsteps.

“When they talk about Walz he’s very relatable. He’s, you know, one of us. And, you know, they just trust him.”

“And I think a lot of people are very tired of the divisiveness and the bitterness and he’s, he’s anything but that.”

There’s plenty of divisiveness in Nebraska.

Even here, deep in the American countryside, you can hear the unsubstantiated assertions that large numbers of immigrants are unlawfully claiming Social Security or engaging in ballot fraud.

One Republican voter admits his belief in such claims is based not on fact, but on what he’s heard, with echoes of JD Vance’s similar justification for his promotion, without evidence, of the allegation that Haitian migrants are eating pets in Ohio.

A soybean farmer tells me that Kamala Harris is a “DEI hire”; another says it is white people who are being discriminated against in today’s America.

Yet, on the Democratic side, there are signs of groupthink too – the bafflement over the choices of their opponents and a readiness to see all Republican voters as motivated by the narrow politics of prejudice.

But there’s something else unique about Nebraska’s electoral system. Its state legislature is nonpartisan, meaning it does not recognise the party affiliations of its elected members nor organise them around formal party voting blocs.

In the city of Hastings, Michelle Smith is out canvassing for a seat in that local legislature.

She’s a Democrat fighting for votes in a very red district, but, she says, the system encourages compromise.

“My own father is one of those people who’s going to vote for Donald Trump, and I understand it,” she tells me.

“I’m a business owner. I paid less taxes when Donald Trump was president. Our prices were lower at the grocery store.”

How does she campaign?

“I bring it down to the local issues. I’m not a national candidate. I’m a local candidate, and I’m running to make things better here in Nebraska.”

For now, Nebraska is very much in the national spotlight.

There’s been a last-minute attempt by the Republican Party not to leave anything to chance, with several lawmakers pushing for a move to make the state a winner-takes-all system.

Barring the completely unexpected, that would mean all the state’s electoral college votes go to Donald Trump.

It foundered, though, on the opposition of a few local Republican senators, who refused to bow to the pressure this close to an election, placing what they saw as the interests of the state – given the rare bit of political leverage the system provides – over that of national partisan politics.

Even Lindsey Graham, the powerful Republican senator, flew in to meet with the holdouts, but to no avail.

“It was interesting,” he’s reported to have said back in Washington. “They have a different system. Everybody’s like a mini-governor.”

Whether or not Nebraska plays an outsized role in November’s deeply divided contest, it may offer something of an alternative to it.

US election live: Latest polls show Harris, Trump tied on election eve

Elon Musk’s $1m US voter giveaway to continue, Pennsylvania judge rules

Trump or Harris? Gaza war drives many Arab and Muslim voters to Jill Stein

Joe Rogan endorses Trump on eve of the election

Trump describes US as an occupied country in dark closing message focused on immigration

Trending

-

The Washington Post7 months ago

The Washington Post7 months agoAre you still registered to vote? How to make sure you’re up to date.

-

Debates8 months ago

Donald Trump Vs Kamala Harris LIVE | The Big 2024 Debate | U.S. Election Latest

-

CNN7 months ago

CNN7 months agoCNN Poll: Harris and Trump are tied in North Carolina, while vice president leads in Nebraska’s 2nd District

-

CNN7 months ago

CNN7 months agoNew York Democrats are desperate to avoid repeat of their 2022 midterm collapse

-

Donald Trump8 months ago

Donald Trump8 months agoWas Harris’s debate performance enough to win over undecided voters?

-

Kamala Harris7 months ago

Kamala Harris7 months agoExclusive: Harris to release new economic proposals this week on US wealth creation

-

Debates8 months ago

US election: Blistering exchanges and fact checking in Kamala Harris and Donald Trump debate

-

CNN7 months ago

CNN7 months agoHarris’ cash edge funds advertising blitz as Elon Musk cuts big check to House Republicans, new filings show